Like all other parts of our society, COVID-19 has profoundly affected the operation of Canada’s Parliament. Members of Parliament and Senators have repeatedly suspended normal parliamentary procedures to quickly pass measures so that the federal government will have the resources needed to respond to the pandemic in an effective and timely manner.

However, democracy is not a luxury, but an essential service. Indeed, MPs across the country report being overwhelmed with requests for help from citizens whose livelihoods and health have suddenly been threatened as a result of the pandemic. Parliament has a vital role to play in holding the government to account for its response to the pandemic and ensuring that these concerns are heard.

Before Parliament is recalled for a second time, this piece examines how Parliament sought to adapt over the course of March relative to the approaches taken in other jurisdictions. In particular, it looks at whether the right balance has been struck between acting quickly to ensure the government has the resources it needs to react quickly while still maintaining as much scrutiny, transparency, and accountability as possible. To help put this review in context, we first review how Parliament operates under normal conditions before looking at its response to COVID-19. A selected timeline of COVID-19’s spread and the government’s reactions to it is also presented in Appendix I.

View a summary of our analysis.

One of Parliament’s major jobs is to hold the Prime Minister and the cabinet accountable to citizens between elections. While cabinet ministers propose most new laws and develop the Government’s spending plans, the government cannot tax, spend, borrow money, or create a new law without the consent of both the House of Commons and Senate. MPs and Senators also have the duty to review or scrutinize how the government actually delivers its proposed programs and services, and to hold the Prime Minister and cabinet accountable for the choices they make.

But MPs and Senators can only do their work if they have enough time and information to effectively evaluate the pros and cons of the Government’s proposed legislation and spending, and if the Government is transparent about how programs are being implemented. To ensure that MPs and Senators aren’t rushed into approving anything that they haven’t had a chance to study, parliamentary procedure breaks down the process of making new laws into a series of stages, each of which is supposed to take place on a different day. Spreading out the process also gives the researchers who support MPs and Senators the chance to produce detailed briefings on the potential impacts of the Government’s proposals. A recent Samara Centre study found that between 2015 and 2019 the average piece of legislation was debated on 11.9 days in the House of Commons and on 15 days in the Senate before passing.

So far, Parliament has taken urgent action in response to the pandemic on two occasions–March 13 and March 24 and25. In both cases, both the House of Commons and Senate suspended their normal procedures to pass emergency legislation. However, the circumstances and outcomes of the two situations differ significantly, and so we’ll look at each separately below.

While concern about COVID-19 was growing, Parliament began sitting on Monday, March 9 as normal. However, as described in the timeline below, the pandemic quickly escalated, and by mid-week it was apparent that Canada would need both social distancing measures and emergency government spending to respond to the pandemic.

Groups of senior MPs and Senators from all parties met on March 12 to negotiate Parliament’s response. Given that MPs and Senators fly to Ottawa from across the country, they decided to help slow the spread of the disease by adjourning Parliament for five weeks until April 20. However, before leaving Ottawa they also needed to ensure that the government had the money necessary to respond to the pandemic, and to deal with urgent matters already under debate, including legislation to give effect to the new United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) Free Trade Agreement.

The negotiations produced an omnibus motion with 16 clauses that was put before MPs the following morning. As well as passing the USCMA implementation bill through all its remaining stages, the motion also passed a never-before-seen piece of legislation, Bill C-12, to allow for government spending during the pandemic. MPs adopted the motion via a procedure called “unanimous consent,” which allows them to override normal parliamentary process and pass legislation in just one step, so long as no single MP disagrees. There was no debate on the merits of the motion, and the motion was adopted before the text of C-12 was presented to the House of Commons.

In addition to being adopted through an extraordinary process, Bill C-12 also gave the government extraordinary spending powers. Although Parliament is supposed to approve all spending before it happens, the Financial Administration Act allows the government to issue “special warrants” to make unexpected spending when the House of Commons has been dissolved for an election and there are no sitting MPs to approve the measures. Bill C-12 amended the Financial Administration Act to allow the government to use special warrant to spend any funds that it needs until June 23, 2020, even though Parliament was not dissolved.

To balance the blank cheque given to the government in Bill C-12, the omnibus motion contained a series of accountability mechanisms, including requirements for the government to report any special warrant issued to the House of Commons and for the Auditor General to review any spending made in this way. After MPs unanimously adopted the omnibus motion, the USMCA implementation bill and C-12 were sent to the Senate, which passed them in a special sitting later that day.

By the following week, it was clear that efforts to contain COVID-19 would have a devastating impact on the Canadian economy, and that further government action was needed. On March 18, Prime Minister Trudeau announced a further $82 billion in COVID-19 response measures. However, implementing the measures required legislative changes to programs such as Employment Insurance that went beyond the spending powers granted by Bill C-12.

The opposition parties supported the Government’s plan, and the Prime Minister recalled Parliament to pass the necessary emergency legislation on March 24. Senior Government and Opposition MPs once again sought to work out a deal among themselves so that the emergency legislation, Bill C-13, could pass in a single day. To reduce the chances of spreading COVID-19, they further agreed that the House of Commons would meet with just over 30 MPs, which would be proportionately allocated among the five parties with seats (Bloc Québécois, Conservatives, Green, Liberal, and NDP). The senior MPs in each party selected which MPs should attend, with a priority given to those who could easily drive to Ottawa. All other MPs were asked to stay away except for the Deputy Speaker and one Assistant Deputy Speaker who would preside over the debate.

However, the cross-party negotiations hit a snag when the opposition parties objected to measures in a draft of Bill C-13 that would allow the government to tax, borrow, and spend any sums of money without parliamentary approval until the end of 2021. Opposition MPs felt that these measures allowed the Government too much capacity to avoid parliamentary scrutiny for too long a period of time.

The emergency session of the House of Commons began at noon on March 24 but was immediately suspended so negotiations could continue. Early the following morning a deal was eventually reached under which the Government agreed to remove the emergency taxation powers from C-13, limit the Government’s power to spend without parliamentary approval until the end of September, and to allow further parliamentary oversight.

The House reconvened at 3:15 AM and another omnibus motion was presented to give effect to the agreement. Specifically, the motion:

MPs once again passed the motion via unanimous consent. They then spent an hour debating the Government’s response to COVID-19 in general terms, and a further 90 minutes specifically debating Bill C-13. The House of Commons ultimately passed C-13 through its final stages just before 6:00 AM and then adjourned. A list of MPs present for the emergency session can be found in Appendix II.

The Senate began its own consideration of Bill C-13 just four hours later. They passed the Bill after two hour of debate and then spent a further 90 minutes debating the COVID-19 pandemic. Senator Yuen Pau Woo, the Facilitator of the Independent Senators’ Group, also attempted to bring forward a motion that would have allowed the Standing Senate Committees on National Finance and Social Affairs, Science, and Technology to meet while Parliament is adjourned to examine the government’s response to COVID-19, but he did not receive the unanimous consent required. The Senators present during the emergency session are listed in Appendix III.

The extraordinary manner in which the bills enabling Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic were passed through Parliament reflected efforts by senior Government and Opposition MPs to balance the government’s need to rapidly spend massive sums while also preserving parliamentary oversight of that spending. However, while the Opposition succeeded in limiting the scope of the Government’s emergency powers and protecting Parliament’s oversight role, they did so at the expense of transparency and inclusive representation.

The two emergency bills adopted by Parliament thus far recognize the gravity of the situation by providing the government with the extraordinary power to spend funds without first seeking parliamentary approval. Nonetheless, Opposition MPs have succeeded in both restricting the duration of these exceptional powers and ensuring transparency and oversight for their use. In particular, the Opposition forced the Government to greatly curtail the financial powers originally proposed in Bill C-13. The Auditor General will also review any spending made through special warrants under C-12, and the Finance Minister must report to the Standing Committee on Finance regarding the use of the powers in C-13.

However, this oversight has been achieved through unconventional means. While the federal Emergencies Act lays out specific provisions for parliamentary oversight of any emergency declaration, the provisions for oversight of government actions under Bill C-12 and C-13 were contained in separate motions passed by the House of Commons in parallel to the bills. Although the measures in the motions ensure the government will be held accountable for its use of these powers, any individual who does not consult the parliamentary record in addition to the text of the legislation will be unaware of the oversight provided.

The oversight measures established for bills C-12 and C-13 also fall short of those laid out in the Emergencies Act. The emergency spending and other powers laid out in that Act are only available if the government specifically declares a state of emergency. However, the Emergencies Act stipulates that both the House of Commons and Senate must be reconvened to ratify the declaration. If the vote fails in either chamber, then the state of emergency is cancelled. Moreover, even if MPs and Senators approve the initial emergency declaration, they still have the right to request a vote in either chamber to cancel the state of emergency at any point.

Bill C-13 allows the government to declare a “Public Health Event of National Concern” giving it the power to spend and make payments to businesses and individuals without further parliamentary approval. The motion adopted by the House of Commons prior to passing C-13 requires the Minister of Finance to report on how the government has used such emergency powers, and members of the Finance Committee can request that the House of Commons be recalled if they are not pleased with the way these powers are used. However, unlike with the Emergencies Act, MPs have no mechanism via Bill C-13 itself or the motion that accompanied it to directly request a vote to cancel the declaration of a Public Health Event of National Concern. Moreover, no mechanism exists for the Senate to actively review either the declaration of a Public Health Event of National Concern or how the powers are used.

Table 1: Passage of Bills C-12 and C-13

Both instances of emergency lawmaking thus far were driven primarily by closed-door negotiations among senior MPs from each party. Once the agreements were reached, these senior MPs expected their backbench colleagues to pass resulting bills and motions without having any input into their content. In the case of Bill C-12, Conservative MP Scott Reid noted in a blog post that the motion passing the bill through all of its stages was adopted before the bill was introduced in the House of Commons, meaning that some MPs who voted for the bill’s passage may not have been able to see its text before doing so. Things were slightly better for Bill C-13, which at least received a first reading an hour before being passed through its remaining stages, but still a far cry from the usual practice under which bills are introduced a day before being debated.

By comparison, the UK government’s Coronavirus Bill was introduced four days before being discussed in Parliament. It was debated for six hours by MPs and seven hours by the House of Lords over a three-day period. As with Bill C-13, the Coronavirus Bill originally would have allowed the UK government to use its emergency powers for more than a year. However, rather than negotiating in a back room, opposition pressure eventually forced the Government to put forward a formal amendment during the debate that created a new mechanism allowing MPs to vote every six months on whether to keep the powers in place. Australia’s Coronavirus Economic Response Package Omnibus Bill was debated on the same day it was introduced, but it too was amended during passage after receiving more than three hours of debate in each chamber of the Parliament.

The transparency around the passage of Bill C-13 was also hindered by the fact that the House of Commons Hansard was not posted until one week after the debate took place. Moreover, given that the House of Commons was only suspended to allow further cross-party negotiations, rather than being adjourned for the day, the debate on C-13 and the accompanying motion that took place in the early hours of March 25th were considered by the House to have happened as part of the March 24th sitting. Anyone hoping to review the debates and the text of the motion adopted may therefore have difficulty locating them within the House of Commons Hansard or Journals.

The process for adopting Canada’s COVID-19 response has so far prioritized the representation of party interests above any other aspect of representation. The small number of senior MPs who negotiated the contents of bills C-12 and C-13 and their accompanying motions could not hope to reflect Canada’s diversity by themselves.

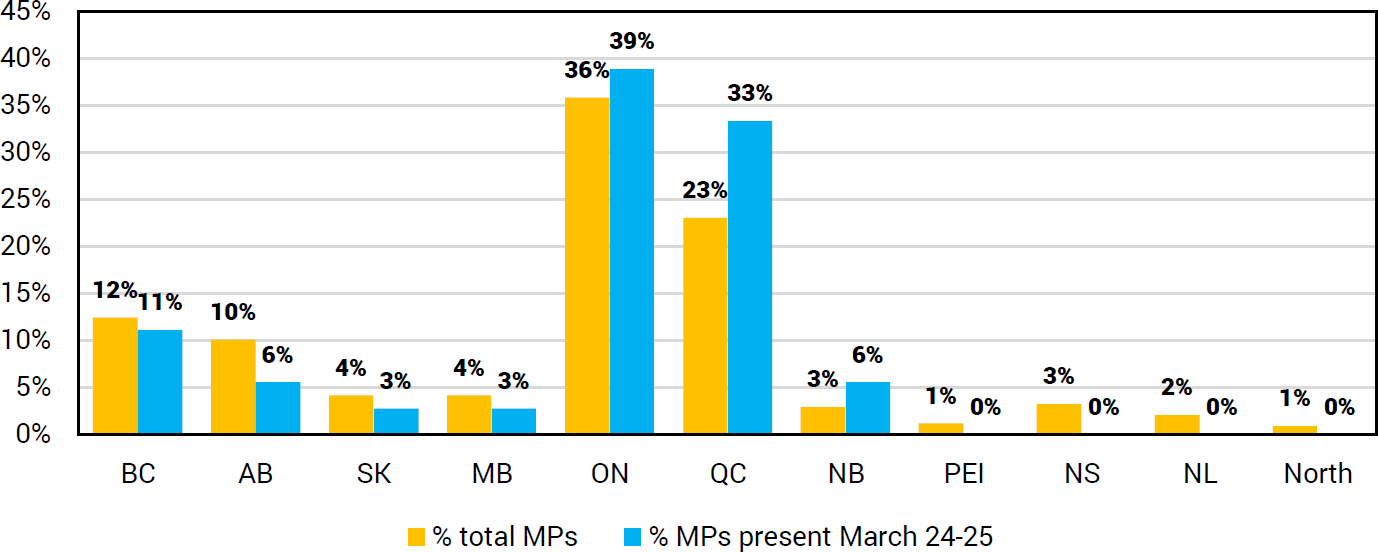

While it is not possible to determine which MPs were present for the adoption of Bill C-12 on March 13, Appendix II and III respectively review the MPs and Senators who attended the emergency parliamentary session on March 24 and 25. Although the balance reflects each party or grouping’s standing in Parliament, the vast majority of MPs and Senators present were from Ontario and Quebec. While limiting travel was reasonable, it was unclear why four MPs and two Senators from BC could attend, yet no parliamentarians were present to raise the experiences of Canadians in the territories, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, or Prince Edward Island. The geographic balance of the parliamentarians serving in each chamber versus those present at the emergency debate is summarized in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: MPs by province versus those present for emergency session on March 24-25

Figure 2: Senators by province versus those present for emergency session on March 25

The lists of MPs and Senators present for the emergency session also reveals that both had a lower proportion of women present than normal. While 29% of MPs and 46% of all Senators are female, women made up just 25% of the MPs and 32% of the Senators at the emergency session.

In addition to limited representation, Canada’s emergency response to COVID-19 has also been tightly controlled by senior officials within each party. As shown in Appendix II, two-thirds (65%) of the MPs attending the emergency session were either party leaders, ministers, whips, house leaders, or parliamentary secretaries. This was especially true of the Liberals, who had just a single backbench Member present.

To some extent this reliance on senior MPs made sense given the effort to restrict the number of MPs in attendance. In particular, if the Liberals were to only have 15 MPs present, then it was reasonable for most of them to be ministers so that they could answer questions from the Opposition.

Yet this party control was not balanced by efforts to survey the views of the backbench MPs who were not present. As detailed by Scott Reid in his blog post, the senior MPs in each party picked which backbench MPs to invite to the emergency session. All others were asked to stay away, a directive Reid interpreted as an affront to his privileges as an MP that would deny him the right to speak on behalf of his constituents. Furthermore, even those Conservative backbenchers who did attend the emergency session reportedly played a marginal role in the negotiations, while Conservative Finance Critic Pierre Poilievre, who phoned into the talks while self-isolating, played a major part.

Canadian politics has long been characterized by tight party control. Yet the emergency response to date has centralized this power even further, with backbench MPs being expected to approve legislation they have not seen and being told whether they can attend Parliament at all. The House of Commons is not an electoral college. The people who sit in it are supposed to play a role. At a time of enormous confusion, when the Government is moving at breakneck speed to enact major measures, ordinary Members likely have an even greater contribution to make as they maintain touch with their communities, and witness the effects of both the pandemic and the response.

Senior Senators were reportedly involved in the March 12 discussions with senior MPs to pass the USMCA, adopt Bill C-12, and adjourn Parliament, but they do not appear to have played a role in the negotiations of Bill C-13. Moreover, since the accountability mechanisms for C-13 were not included in the text of the bill itself, but rather through the accompanying motion passed by the House of Commons, Senators have no ongoing way to scrutinize how the emergency powers that it grants are utilized.

Notably, Senator Woo did seek unanimous consent to present a motion to allow Senate committees to meet via teleconference or videoconference while Parliament was adjourned to scrutinize the government’s response to the pandemic. However, some Senators objected, and so the motion failed. Moreover, even if it had passed, the motion would not have allowed the committees to vote to reconvene the Senate in the same way as the parallel motion adopted by the House of Commons. In contrast, the Emergencies Act gives both the House of Commons and Senate the same power to oversee the government’s emergency actions.

The agreement to allow the House of Commons Standing Committees on Finance and Health to meet by teleconference or videoconference represents a major step forward in the use of technology to enable ongoing oversight by Parliament. While the initial meeting had technological difficulties with simultaneous translation, these challenges will hopefully be worked out with practice.

However, further steps are needed to ensure that MPs and Senators unable to drive to Ottawa can still be represented in debates when Parliament is recalled for further legislation. Otherwise, future emergency sessions will continue to exclude vital perspectives from different regions of the country.

January 23 – China quarantines city of Wuhan

January 25 - First case of COVID-19 found in Canada

January 30 – World Health Organization (WHO) declares COVID-19 a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”

February 5 – Hong Kong closes most border crossings, imposes quarantine on all visitors from mainland China

February 6 – Government begins evacuating Canadians from Wuhan; quarantine centre created at CFB Trenton

February 15 – Government announces plan to evacuate Canadians on Diamond Princess cruise ship from Japan

February 23 – South Korea announces school closures

February 26 – Canada’s Deputy Chief Public Health Officer tells House of Commons Health Committee that social distancing may be needed to deal with pandemic

February 27 – Japan announces school closures

March 3 – Government announces $26 million in research funding for COVID-19

March 4 - Government creates COVID-19 cabinet committee; Bank of Canada cuts interest rates to deal with economic impact

March 8 - Government announces plan to evacuate Canadians on Grand Princess cruise ship from California

March 9 – Outbreak at BC nursing home leads to Canada’s first COVID-19 death; MP Anthony Housefather enters self-isolation; Italy announces countrywide lockdown

March 11 – WHO declares global COVID-19 pandemic; Government announces initial $1 billion in emergency measures

March 12 – Sophie Grégoire Trudeau tests positive for COVID-19; Prime Minister Trudeau enters self-isolation; US suspends flights from Europe; Ontario closes schools until April 6

March 13 – Parliament passes emergency legislation, adjourns until April 20

Copyright © The Samara Centre for Democracy 2020

PUBLICATION DATE: 2 April 2020

CITATION: Paul EJ Thomas 2020. “Parliament Under Pressure: Evaluating Parliament's performance in response to COVID-19.” Toronto: The Samara Centre for Democracy.

EDITORS: Michael Morden, and José Ramón Martí

This is the first edition of the Samara Centre’s Democracy Monitor, an ongoing research series exploring the state of democracy in a state of emergency.